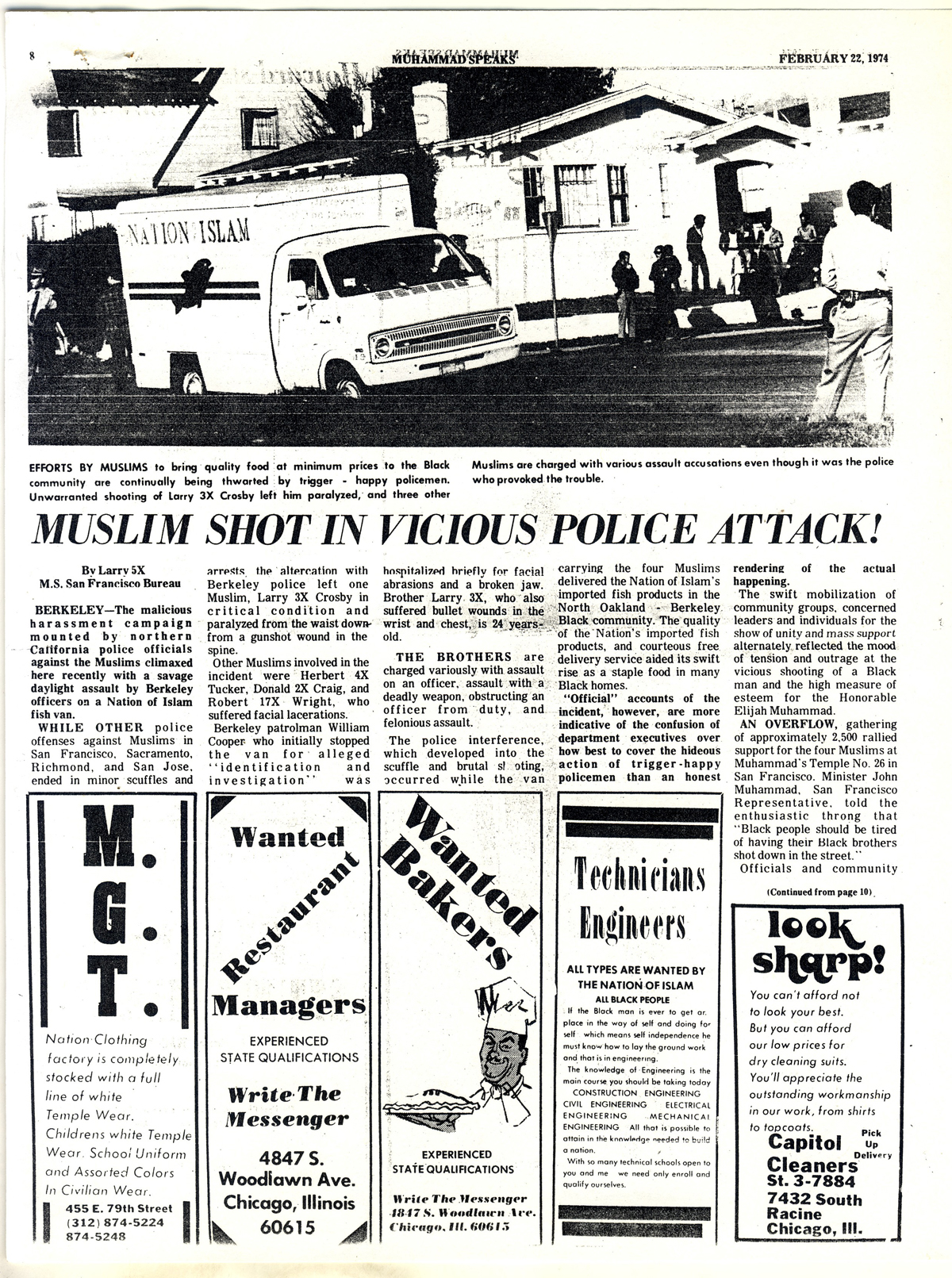

My correspondence with Brother Khalid Waajid began in 2019, a few years after he sent me an archived Muhammad Speaks newspaper article about a Berkeley police shooting he’d been the victim of in 1974. I read the article and looked at the photos, in which Khalid (then named Larry “3X” Crosby) lay on the concrete after being shot three times. The article and photos reminded me of countless incidents of contemporary police brutality against African Americans, but unlike many of those tragic cases, Brother Khalid survived. I saw him throughout my childhood and life, always in his wheelchair, smiling jovially with a mini-DV camera in his hand, recording the Masjid Waritheen community in East Oakland. At the Oakland premiere of my feature film Jinn, he attended and embraced me with open arms.

I began to wonder about his journey through early life, the Nation of Islam, that police shooting, Orthodox Islam and then as a videographer, archivist and documentarian of the Muslim community in the Bay Area. After he sent me that Muhammad Speaks newspaper article about the police shooting that left him paralyzed, I asked him if he’d be interested in sitting down for a short documentary interview on his life. He was excited and receptive to the idea, and we’d planned to do it.

But over the course of the next several years, we never got to sit down for that documentary interview, though we kept in contact. Life swung us all in unimaginable directions through the COVID-19 pandemic. When I learned of Brother Khalid’s recent passing at age 75, I sat on the phone with my father, frozen with sadness. I also reflected on his legacy of communal preservation. In our current political climate, where Islamophobia and hatred have become parts of daily life, Brother Khalid’s videos remind us of the beauty, perseverance and light that we carry. Because of his steadfast documentation, the Muslim community’s presence in the greater Bay Area will never be erased.

For four decades, Khalid filmed major community events during times of celebration, grief and everything in between. “He was doing it on his own,” says his close friend Abdul Raoof Nasir, a Muslim Sheikh. “He would make a short film on someone who died. He would make a short film on [celebrations like] the Evening of Elegance. He would do those things, and I don’t know if he was ever paid. All of this was done as volunteer work. He was quite phenomenal.”

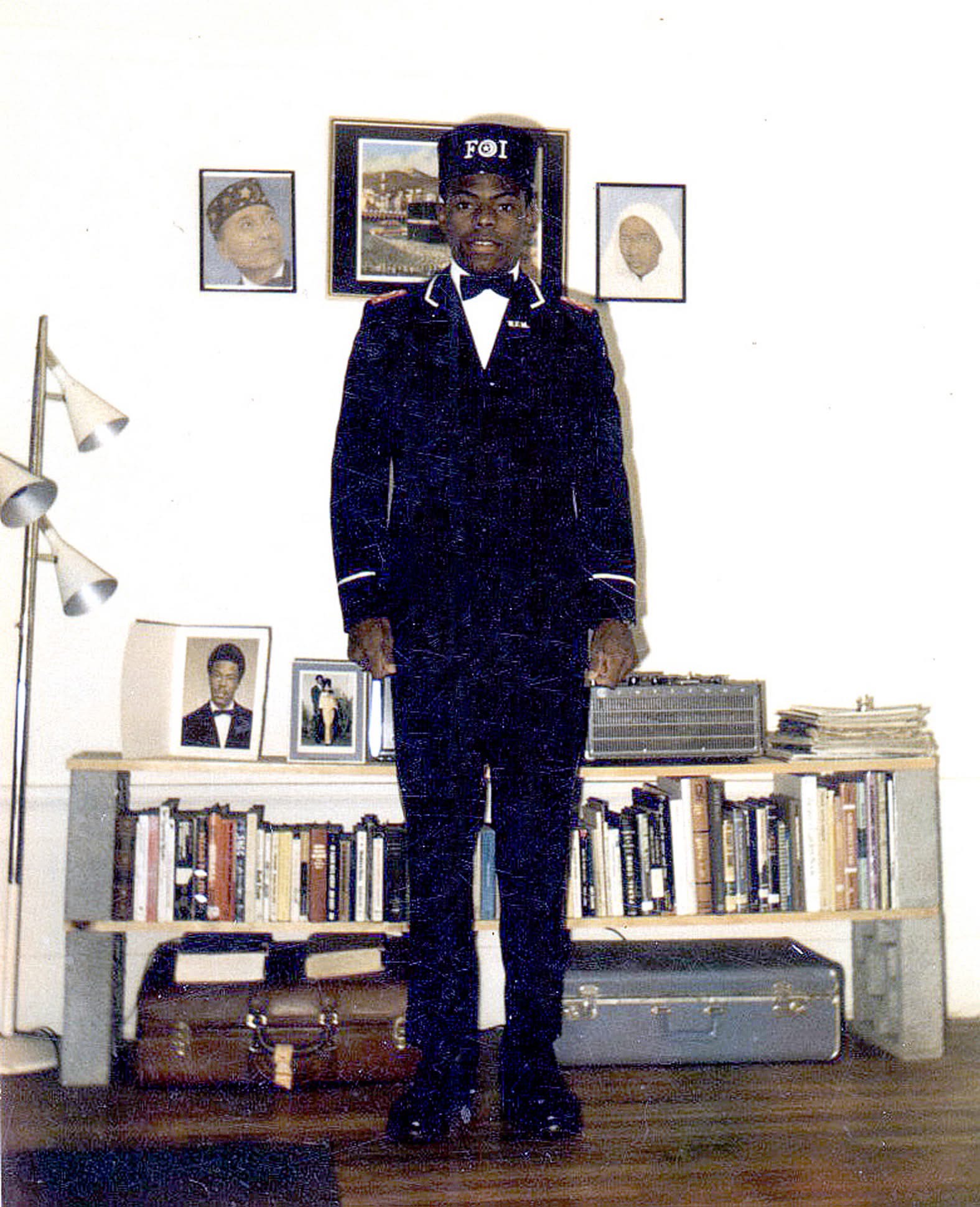

Brother Khalid was an artist from an early age: His first love was architecture, but his white teacher steered him towards graphic design. While a student at Laney College, he became interested in media studies and videography, strengthening these passions throughout his life. He began documenting his life as a young member of the Black Panther Party in the 1960s.