Gas stoves emit a host of pollution that is unhealthy for you, from gases that irritate your lungs to carcinogens.

As a climate reporter who covers indoor air quality, I’ve read study after study about the negative health impacts of cooking with gas. Not to mention their impact on the planet.

And a majority of Californians, roughly 70% (PDF), use gas stoves. They’re one of the only gas appliances we use that vent inside our homes. National and state codes dictate that gas furnaces, water heaters and dryers all vent their exhaust outside.

There was a lot of noise around the health of gas stoves last year after research came out, attributing roughly 13% of current childhood asthma cases in the U.S. to the appliances. Reports circled that a member of the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission said a ban on gas stoves was on the table. Conservatives falsely claimed the Biden administration was out for the appliances, and a Republican Congressman wrote on social media platform X that his stove would need to be pried “from my cold dead hands.”

So I wanted to see what really happened in my own home, a place I share with my husband and two kids, one of whom has asthma. Just how bad was our own gas stove?

I invited over two scientists from research nonprofit PSE Healthy Energy, Eric Lebel and Yannai Kashtan, who’ve also published extensive research on the topic.

They suggested we run our own experiments: to test the air in my home when cooking with a plug-in induction cooktop versus a gas stove, to cook with the hood on versus off, and to simulate preparing a bountiful holiday meal with multiple burners ablaze and the oven on high.

While I had some guesses about what would happen, the results still surprised me.

A mobile lab

Lebel and Kashtan rolled up on a rainy and cold November morning with what was essentially a mobile air testing lab in the back of a car.

They unlooped three long, clear tubes and wove them from the car, through our front doorway, and into three separate rooms: the kitchen, living room and kids’ room. The open ends of the tubes pulled air from inside the house to analyzers in the back of the car outside.

To eliminate any false readings from other gas sources, we made sure to turn off the furnace and water heater. The car with the analyzers, while parked and off, was electric.

Gas stoves can emit a whole bunch of pollutants, including carbon monoxide and methane.

While we measured those gases, we largely focused on nitrogen dioxide, which irritates your respiratory system, and benzene, a carcinogen. These are the two pollutants with demonstrative health effects that scientists at PSE Healthy Energy find most frequently.

The World Health Organization sets guidelines for safe exposure to nitrogen dioxide and benzene:

- Nitrogen dioxide, exposure for a short time of an hour: 100 parts per billion

- Nitrogen dioxide, chronic exposure: 5.3 parts per billion

- Benzene: “No safe level can be recommended”

That means if I’m baking cookies and frying potato pancakes and spike the level of nitrogen dioxide in the air up past 100 ppb, WHO recommends I only breathe that in for an hour.

And if I’m always breathing in more than 5.3 ppb, I need to figure out some better form of ventilation.

Nitrogen dioxide “is one of the clearest things that negatively impacts our respiratory health,” said Carlos Gould, assistant professor at UC San Diego School of Public Health. “It makes your respiratory system, your throat, your lungs really angry.”

Studies dating back to the 1970s have found an association between nitrogen dioxide and respiratory issues like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

As we move through the world, we’ll inevitably be exposed to all kinds of pollutants. These guidelines can help us try to minimize our risks of exposure. You’re not doomed if you breathe in a high amount of nitrogen dioxide for over an hour, but it would be better if you didn’t.

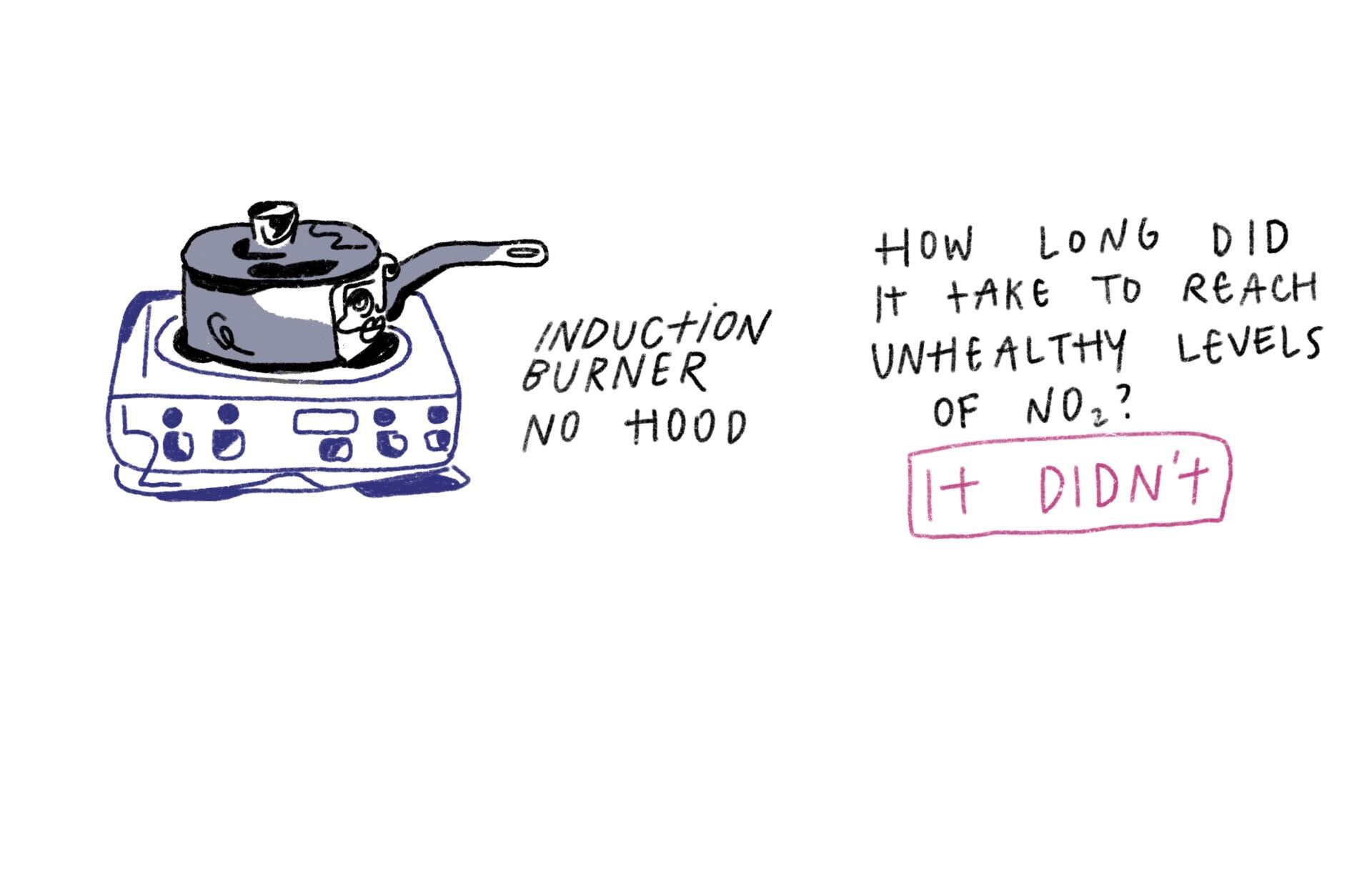

Experiment #1: Induction cooktop, hood off

We filled up a large pot with six cups of water. We turned a portable, plug-in induction cooktop on high and waited. No windows were open, and the hood was off.

We filled up a large pot with six cups of water. We turned a portable, plug-in induction cooktop on high and waited. No windows were open, and the hood was off.

The charts tracking emissions were all flat: nitrogen dioxide, benzene and other pollutants remained the same. The only thing to nudge up slightly was carbon dioxide, and that was from us, three people and one dog, exhaling in the kitchen.

Exceeds WHO’s chronic nitrogen dioxide guideline (5.3 ppb): did not exceed

Exceeds WHO’s short-term nitrogen dioxide guideline (100 ppb): did not exceed

Changes in benzene level at 15 minutes: 0

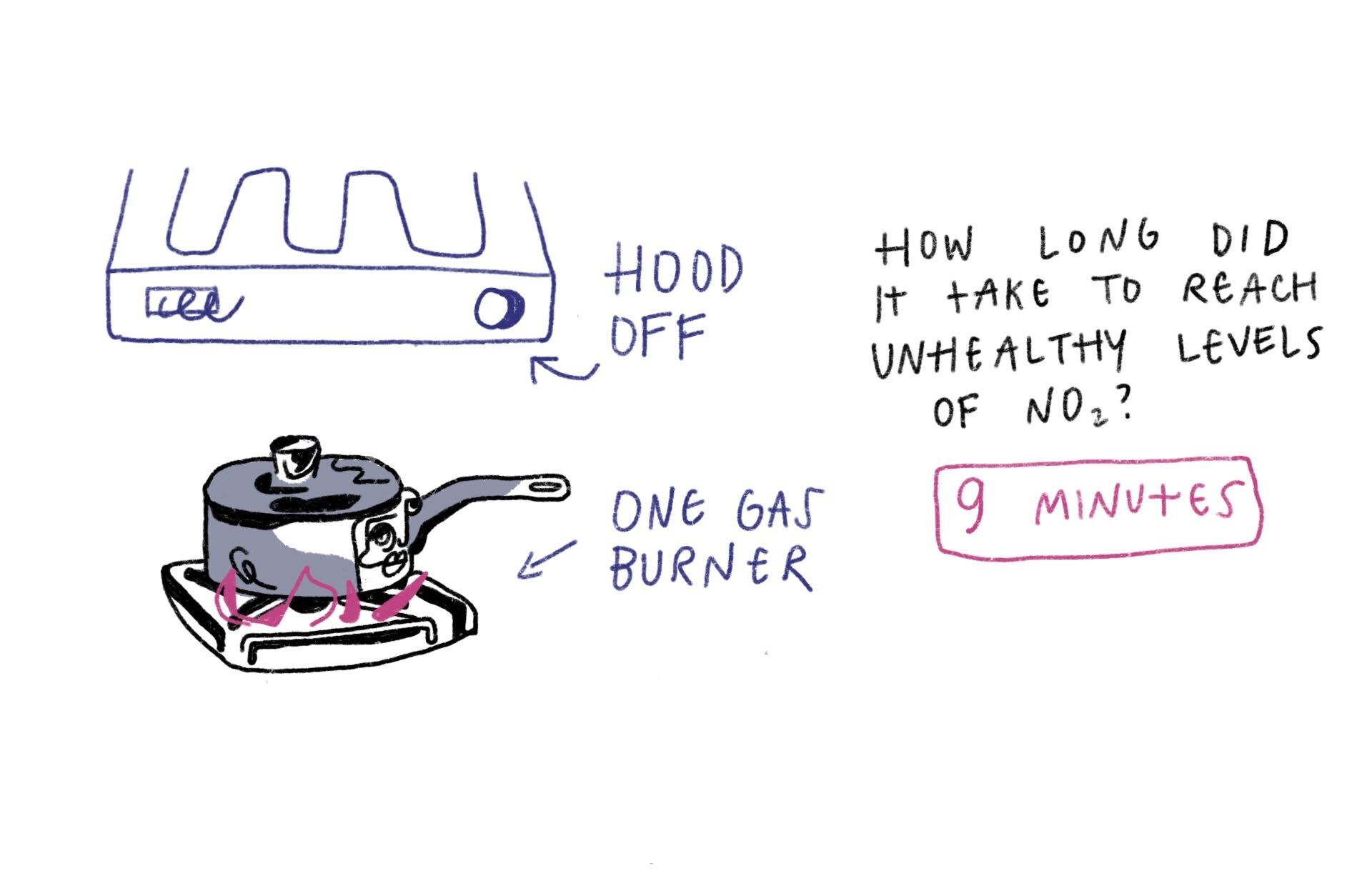

Experiment #2: One gas burner, hood off

We set up the same pot with six cups of water, setting one burner on the gas stove on high to boil the liquid. No windows were open, and the hood was off.

We set up the same pot with six cups of water, setting one burner on the gas stove on high to boil the liquid. No windows were open, and the hood was off.

Nitrogen dioxide levels shot up fast, surpassing chronic WHO guidelines for chronic exposure in minutes. Benzene remained low compared to numbers scientists have measured from other stoves but still increased.

The gases quickly spread throughout the house, including our kids’ bedroom. “What we find pretty consistently is that the pollution spreads pretty evenly, pretty quickly,” said scientist Kashtan, who’s led several studies about the pollution created by gas stoves.

Exceeds WHO’s chronic nitrogen dioxide guideline (5.3 ppb): 9 minutes

Exceeds WHO’s short-term nitrogen dioxide guideline (100 ppb): 33 minutes

Changes in benzene level at 15 minutes: +0.15 ppb

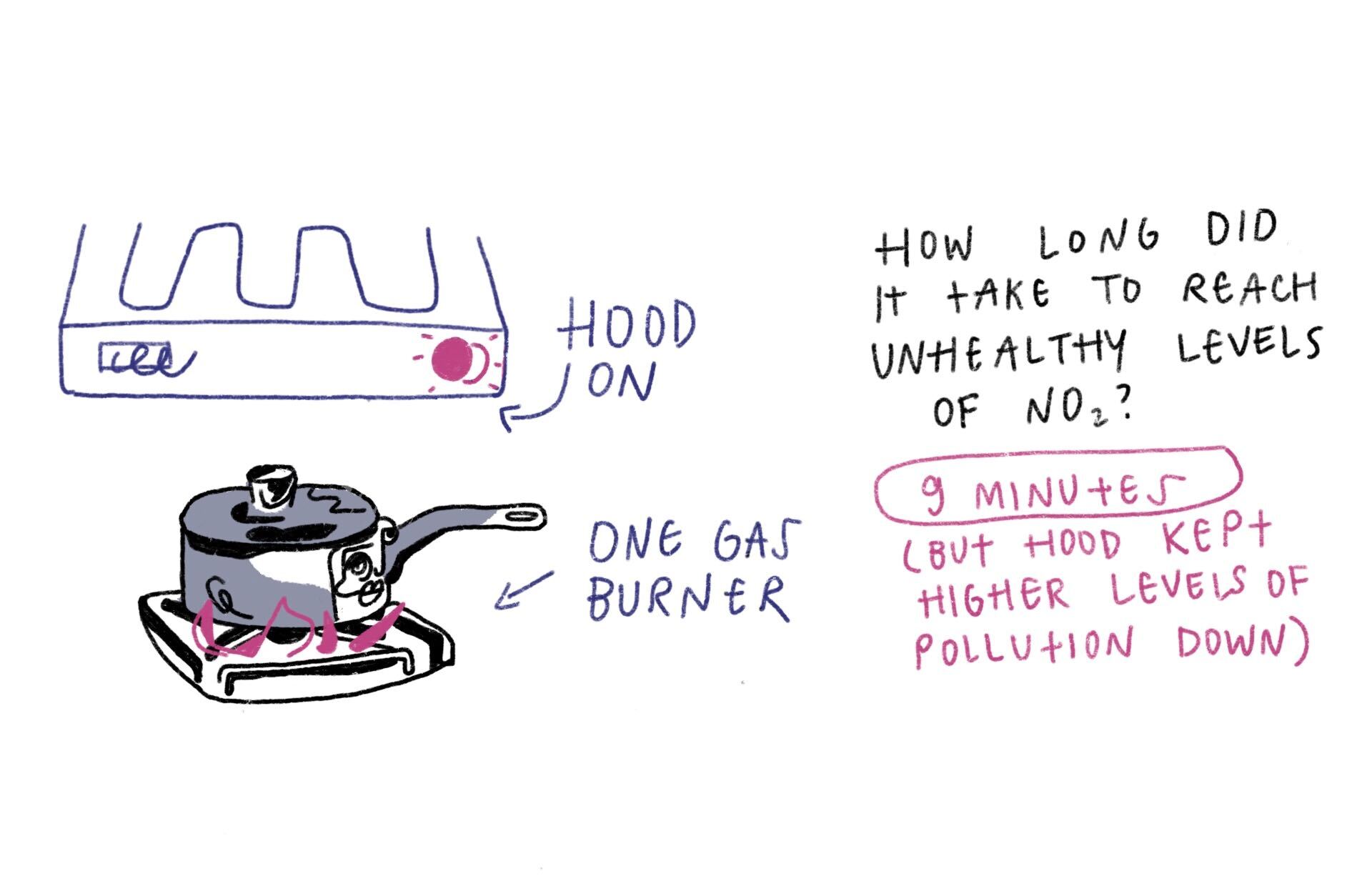

Experiment #3: One gas burner, hood on

We aired out the house and set up the same experiment again but with the hood on.

We aired out the house and set up the same experiment again but with the hood on.

Initially, nitrogen dioxide increased quickly but then slowed significantly. The hood seemed to hold the higher concentrations of nitrogen dioxide down by at least a half, and in some cases more.

Exceeds WHO’s chronic nitrogen dioxide guideline (5.3 ppb): 9 minutes

Exceeds WHO’s short-term nitrogen dioxide guideline (100 ppb): did not exceed

Changes in benzene level at 15 minutes: +0.05 ppb

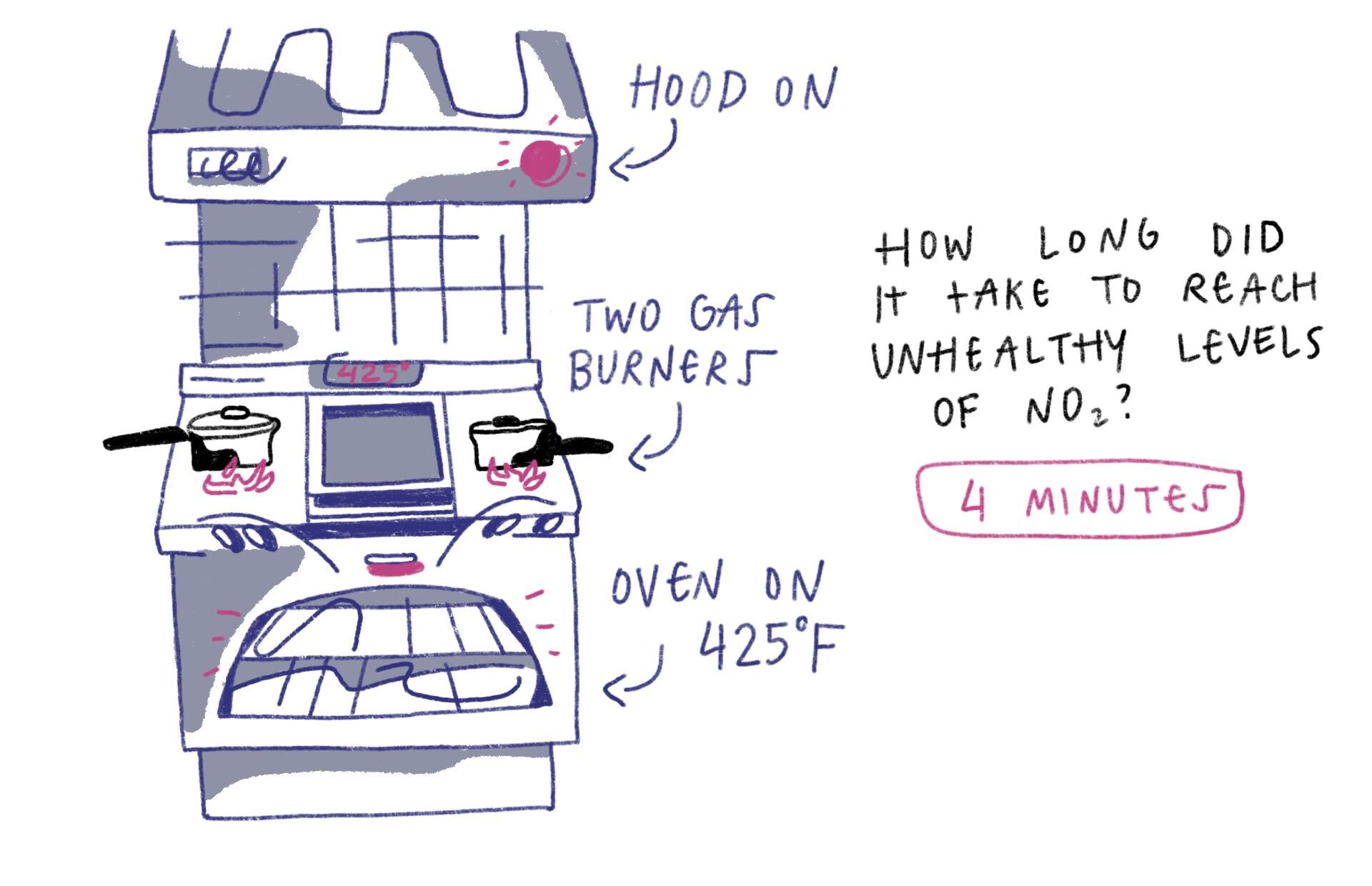

Experiment #4: Holiday cooking with oven and two gas burners, hood on

With the oven on at 425 degrees Fahrenheit and two burners alight, the pollution levels bounced up within minutes despite the hood venting air outside.

With the oven on at 425 degrees Fahrenheit and two burners alight, the pollution levels bounced up within minutes despite the hood venting air outside.

Levels of nitrogen dioxide ballooned above what is healthy, even temporarily. In our particular home, the pollution continued to accumulate in our living room, where presumably people would be gathering before a holiday meal.

Exceeds WHO’s chronic nitrogen dioxide guideline (5.3 ppb): 4 minutes

Exceeds WHO’s short-term nitrogen dioxide guideline (100 ppb): did not exceed but hovered up in the 90s

Changes in benzene level at 15 minutes: +0.06 ppb

The takeaways

Overall, indoor air pollution was nearly zero when cooking with induction. The next best option was using just one burner with the hood on.

A single burner without the hood on and two burners plus the oven with the hood on both spiked pollution quickly.

Our experiments showed me the value of limiting how often I use our gas stove and that I could reduce the risk of exposure to harmful gases by using a plug-in single burner cooktop or other electric appliances like a slow cooker more frequently than the gas range. It reiterated the importance of turning on the hood (though it is noisy) and ventilating the house, even when it’s cold.